For many of us, Colorado’s wildlife is a big part of why we choose to live and play in this beautiful state. They inhabit our wildlands, our neighborhoods, and are even known to visit our backyards from time to time. Colorado has more than 960 species of wildlife, making it home to one of the most diverse and abundant wildlife populations in North America. These animals remind us that we’re part of something much larger and that Colorado is still very much a wild place. But did you know that their existence and health aren’t by chance? Without science and what is known as wildlife conservation — Colorado would not be the home to wildlife it is today.

A Wild Past

A few generations ago, wildlife faced an uncertain future. In the mid to late 1800s, as settlers descended on the area, overhunting and water pollution had a harsh impact on deer, elk, pronghorn, buffalo, bear, birds and fish. Many feared that some of these species would never recover. In 1870, the Colorado Territorial Legislature passed its first wildlife protection laws; and in 1879, the first state wildlife protection agency was formed. The Colorado Division of Wildlife, which would later become Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW), worked to set and enforce limitations, including banning the use of nets for fishing, setting hunting seasons and bag limits, and even prohibiting hunting of pronghorn and bighorn sheep for over 50 years. These calculated efforts from scientists, hunters and anglers were part of a larger movement that would become the way we protect and care for wildlife in the United States and Canada. As more people understood the value of conserving our natural resources and wildlife, a new management and funding model was set — eventually named the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation (NAMWC).

The next time you see a majestic moose drinking from a creek or a bald eagle plucking a trout out of water — in part, you can thank the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The NAMWC has several principles, the most important being that wildlife is held in the public trust, meaning wildlife belongs to all citizens and should be managed for the benefit of all people (whether it’s for wildlife viewing, hunting, fishing, etc.). It states that wildlife management and policy should be set through the use of science. The model also calls for hunting and fishing to be open to all citizens, and uses the funds from these activities to pay for wildlife management. Today, and for the past 125 years in Colorado, the majority of wildlife management funding has come from the sale of hunting and fishing licenses. These tens of millions of dollars each year pay for the scientific management of wildlife in Colorado.

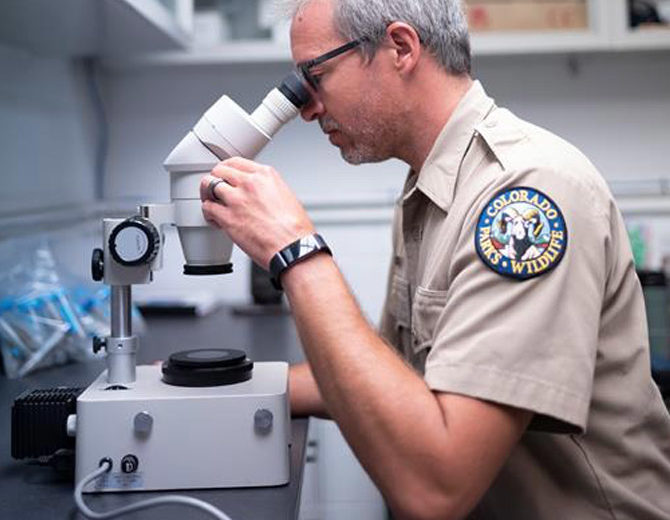

Science Is Personal

For Colorado Parks and Wildlife, the state government agency charged with managing fish and wildlife, science is personal. It employs all kinds of scientific personnel, such as terrestrial and aquatic biologists, who manage numerous species like deer, elk, sheep, moose, trout, warm-water fish and amphibians. It has dedicated researchers who focus on the management of singular species, interactions between species, habitat uses and human interaction. Even its district wildlife managers, who perform law enforcement, are required to be a biologist first.

These dedicated wildlife professionals work together to manage populations and keep our wild animals on the landscape for generations to come. While science guides the strategy, it’s these individuals’ passion for wildlife that ensures that their future is bright.

You Can Count on CPW

Managing wildlife populations means knowing how many animals there are to begin with. But how do you count these elusive creatures through thick forests and even below the water? You guessed it — using science.

Getting accurate population estimates is a critical piece of managing each species. The agency uses helicopters and planes annually to count big game from the air. To better understand bighorn sheep, it will perform what is known as “sheep captures,” where large nets are used to quickly catch, count and tag sheep. Later, the team fits some of the sheep with radio collars that transmit data, giving biologists a better understanding of movement patterns and mortality rates. For fish, teams use electrofishing equipment that temporarily and safely shocks the fish using electricity so that they can be netted, weighed and counted before being put back into the water. This data helps set fishing regulations on a stretch of river or lake, and helps influence where the agency puts the nearly 100 million fish that it raises each year to be stocked in the state’s waters.

After completing all of this work to better understand each species’ population and overall health, the real work begins. Managing each species might require making habitat improvements, helping fish and wildlife reproduce, or in some cases maintaining or reducing populations through the use of hunting and fishing. For example, after biologists record and analyze populations of species such as elk, deer and moose in certain zones, biologists set how many hunting licenses are issued for each area. While the hunters who go out in the field to harvest an animal might be doing it for recreation and for providing food for themselves and their families, they’re also playing an important role in keeping herds healthy and preventing overpopulation. When a certain area becomes overpopulated with a species, they are more susceptible to starvation, chronic wasting disease and other health threats.

Life Finds a Way — Through Science

When Jurassic Park’s Dr. Ian Malcom (played by Jeff Goldblum) says “Life, uh, finds a way,” he isn’t wrong. The only caveat is that, in our current era, wildlife thrives through wise scientific management. Unfortunately, there are a number of wildlife species that have disappeared from the Colorado landscape. Luckily, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, with help from federal and nonprofit partners, has managed to bring some of them back.

In the late 1800s, Colorado’s lynx population started to plummet. Landowners poisoned the cats to prevent damage to livestock, and trappers killed them without regulation for their fur. By 1974, the last known lynx was illegally trapped near Vail, a year after the state listed the lynx as an endangered species. Fast forward to 1997, CPW undertook what was to become one of North America’s most high-profile carnivore reintroductions to date — bringing lynx back to Colorado.

In 1999, CPW brought the first 41 lynx from Canada and Alaska to the San Juan Mountains in southwest Colorado, where river valleys, rugged mountains and adequate prey provided the perfect habitat. More than 200 lynx were brought to the area over several years. Biologists tracked these cats closely using telemetry collars that reported their location. By 2006, the reintroduction of lynx was deemed a success due to a self-sustaining population in Colorado. Today, CPW researchers work toward determining and maintaining the long-term success of the reintroduction.

We’re Not Done

Thankfully, for Colorado, a methodical and scientific approach to wildlife management has brought species back from the brink of extinction, returned fish to rivers where none could be found, protected and increased populations — all while providing world-class hunting, fishing and wildlife viewing. However, the work is never over. Unfortunately, there’s still a list of threatened and endangered species, and the agency continues to work with partners to protect and bring these animals back. CPW’s researchers continue to work on myriad projects: from analyzing wildlife’s impact from bark beetle infestation, to preventing plague in prairie dogs and their predators, to understanding and better managing black bear interactions with urban environments. Luckily, we can count on the state’s dedicated wildlife professionals, a model for protecting and restoring these majestic creatures, and the science and technology that will keep them on the landscape for generations to come.